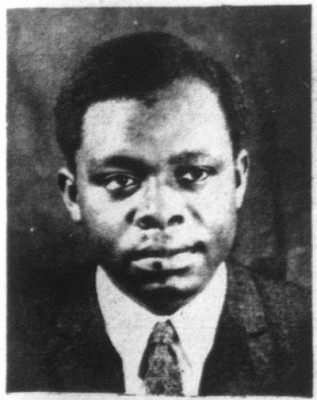

Joseph Robert ‘Sepp Meier’ Bikobbo Mugayo (c.1942-76)

Ugandan intellectual and political advisor

Bikobbo was an anti-imperialist intellectual who hailed from Uganda’s lacustrine margins. He came to prominence amid the radicalism of the mid-1960s. His experience of higher educational abroad was extremely varied, taking in Leeds but also a couple of more unusual and quite disparate destinations in Zagreb and Nashville. An uncommon combination of credentials, insights, and connections elevated him to a perilous position behind the scenes at the presidential centre of power under successive regimes.

Between imperialisms

Bikobbo was born into the Badogimo clan of the Gungu ethnic community in about 1942. His family lived in Bugungu, in what is now Buliisa District, on the shores of Lake Albert at the low-lying north-western periphery of the multi-ethnic historical polity of Bunyoro. Bikobbo was the youngest son of Gabriel Mugayo Galende, a man of modest means by the standards of his community, which had grown wealthy from fishing. But Galende was willing to entertain his son’s educational ambitions. Reward came in the form of corporate sponsorship, a public relations strategy that Western multinationals were busy expanding owing to the risky conjuncture of the Cold War and decolonisation. The largesse of Shell Company took Bikobbo to senior secondary school in Masindi in the early 1960s.

Bikobbo’s final few years at school were Uganda’s first years of independence, during which a struggle broke out within the ruling political party, the Uganda People’s Congress. The conflict culminated in 1964-1965 in the crushing of the party’s leftist, anti-imperialist wing by the right. In the immediate aftermath, the relatively unscathed Prime Minister Milton Obote ostentatiously took up the left’s radical mantle, making Uganda the first non-communist country to formally denounce US military intervention in Vietnam.

Bikobbo arrived at the University of Leeds in the mid-1960s, increasingly politicised by these ideas and events. In this West Yorkshire city, several other prominent East Africans were already becoming radicalised on the margins of a thoroughly left-wing student body expressing increasingly fervent opposition to the Labour government’s pro-American position on Vietnam. Bikobbo left Leeds in 1968 with a first-class honours degree and overtly anti-imperialist politics, of a seemingly non-Marxist variety. Early in 1968 he wrote a letter to the editor of US magazine Newsweek to condemn the ‘savage’ hypocrisy of US intervention in Asia.

Later that year, Bikobbo began a course in Political Science and Administration at the University of Zagreb in the socialist republic of Croatia, in Yugoslavia. It was not the easiest experience in some respects. In this republic, the federation’s wealthiest, African students encountered not only language issues and racism, they also had to contend with a Croat ethnic secessionism reinvigorated by political liberalisation. A dark joke, later recorded by sociologist Christie Davies, presented African students as feeling uncomfortably at home in this context:

Two African students met in their home town. One was a graduate of the University of Belgrade and the other of Zagreb University. They began to quarrel over some trivial issue. Finally, one shouted at the other, “Go fuck your Serbian mother”. The other replied: “Huh, go fuck your Croatian mother”.

But Yugoslavia nevertheless endured as a beacon of anti-imperialism. After breaking with an Eastern Bloc dominated by the Soviet Union in the late 1940s, President Josip Broz Tito had begun an experiment with market socialism and took a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), hosting its first summit in 1961. As the decade went on, Tito articulated increasingly forthright critiques of US foreign policy and massively expanded co-operation with the newly independent and non-aligned states and liberation movements of Africa and Asia. Zagreb had for several years been home to an International Student's Club of Friendship and the Africa Research Institute by the time Bikobbo arrived. In 1968, the city had also witnessed a sustained period of anti-war and anti-imperialist protest co-ordinated by the Yugoslav Student League.

The Intelligentsia Agency

Bikobbo returned home in 1969 to a position in the Ministry of Information, Broadcasting and Tourism. He spent little time in this role. Almost immediately his superiors dispatched on a short training course in Sweden organised by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation. And it was not long before the Zagreb graduate was on the radar of figures closer to the heart of the Obote administration. From about 1968, Tito’s socialist one-party state had emerged as one of Uganda’s principal political and economic partners and models in Europe; Obote’s brand of centralising authoritarian nationalism began to combine an increasingly explicit foreign policy commitment to NAM and a domestic policy shift known as the ‘Move to the Left’.

The regime increasingly sought to contain and exploit radical graduates by means of employment in the Research Secretariat of the Office of the President. This unit had been formed in 1968 under Ali Picho, a young man recently returned from studying law in Moscow, who was joined by London-trained Edward Rugumayo and Ateker Ejalu. Around mid-1969, however, all three men had left or, owing to political disagreements, been pushed out by senior civil servants. Like fellow young graduate Yoweri Museveni, Bikobbo was among the replacements recruited in 1970 by the Secretariat, now under an ex-diplomat called Wilson Okwenje.

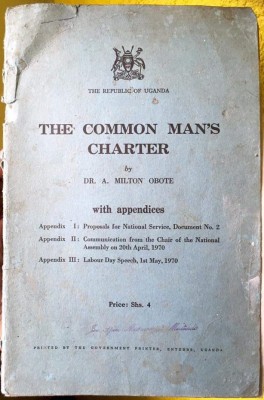

Okwenje later recalled that the Secretariat at this time served Obote as ‘a sort of in-house think tank’. It was also an increasingly pedagogical organisation – Bikobbo in 1970 gave lectures at elite schools on the merits of the Obote’s new policy blueprint, the Common Man’s Charter. But the unit also operated in ambiguous relation to Uganda’s increasingly controversial intelligence organisation, the General Service Department (GSD), which had been established by administrative fiat by Obote in mid-1964 and placed under the authority of his cousin, Napthali Akena Adoko, a lawyer and anthropologist. Proximity to Obote and the praetorian GSD proved a serious liability for employees of the Research Secretariat in January 1971 when figures in the army seized power while Obote was out of the country.

Between America and Amin?

Around the time of the coup d'état, Bikobbo secured a scholarship for a political science Master’s degree course at the rather conservative Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. He studied there for about a year under Alex Dragnich, a specialist on Yugoslavia and political propaganda, and John Dorsey, who worked on public administration in the global south. The cover page of Bikobbo’s Vanderbilt thesis reveals something of his preoccupations away from Uganda’s high politics. Perhaps as an irreverent joke, Bikobbo submitted his thesis under a full name that included ‘Sepp Meier’, presumably in reference to the famous Bayern Munich goalkeeper who had starred in the 1970 World Cup with the West German national football team.

While many of the figures connected to Uganda’s ancien regime remained in exile, Bikobbo returned in May 1972 to take up a post in the Office of the President. The influence he came to exercise over Amin is difficult to assess. In letters to Nashville, Bikobbo claimed to be attempting to resist the shift in Amin’s alliances away from Israel and the West; but some of Bikobbo’s colleagues, later interviewed by journalist Fred Guweddeko, maintained the opposite to have been the case. At any rate, Bikobbo’s foreign connections made him particularly vulnerable amid the regime’s paranoid spiral of violence. Bikobbo appeared in Nairobi in late 1973 after escaping torture and experiencing the death of his son, according to his letters to Dragnich. But by quite a turn of events, within about a year Bikobbo was back at Amin’s side as Principal Assistant Secretary. A short while later he had a child with Princess Dina Kigga, the sister of Buganda’s exiled ruler, or Kabaka, Ronald Mutebi.

Not long after Bikobbo returned to the fold, his life was cut tragically short. The mouthpiece of the military government, the Voice of Uganda, named him as one of four Ugandans who died on 13 January 1976 in a military helicopter crash in eastern Mbale, during the state visit of President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire. Bikobbo was just 33 years old. His wife, the mother of four of his children, Looyi Mulooci went to the UK soon after. In Guweddeko’s account, Bikobbo’s death was pivotal event in regard to Amin’s foreign policy.

Primary Sources

- Dragnich Papers, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford, USA.

- Office of the President, Uganda National Archives, Kampala, Uganda

- Records of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and predecessors, the National Archives, London, UK.

- Ruth Mwayi, ‘The common man plays many roles’, Uganda Argus, 29 October 1970.

- ‘News in brief’, The Times, 16 January 1976.

- Robert Seppmeier Bikobbo-Mugayo, ‘Problems of African political development: tribalism, leadership, military interventions and unity’, unpublished MA dissertation (Vanderbilt University, 1972).

- Akena Adoko, From Obote to Obote (New Delhi, 1983).

- A.M. Kirunda-Kivejinja, Uganda: The Crisis of Confidence (Progressive Publishing House, 1995).

- Wilson Okwenje, ‘He had a knack to enrage, baffle political opponents’, in (ed.) Omongole R. Anguria, Apollo Milton Obote: what others say (Kampala, 2006), pp. 36-41.

- Fred Guweddeko, ‘Luwum Death: Eyewitness Account Amin Shot Archbishop Luwum’, The Monitor, 18 December 2006.

Further reading

- Tertit Aasland, On the Move to the Left in Uganda 1969-71 (Uppsala, 1974).

- Uganda, The Report of Commission of Inquiry into Violations of Human Rights: Volume IV (Kampala, 1995), pp. 3835-3838.

- Yoweri Museveni, Sowing the mustard seed : the struggle for freedom and democracy in Uganda (London, 1997).

- Charles Onyango Obbo, Ear to the ground (Kampala, 1996), p.13.