This teaching resource provides introductory texts accompanied by comprehension and reflection questions. It is intended to be used by teachers and students at school (senior) and undergraduate level, in dialogue with the research-based biographies published on this website.

The resource was compiled by Ismay Milford and Anna Adima, with the help of Shamya Merali, Natasha O’Dowd, Lois Adams, and the 'Another World?' team. It is free to use and share, but please always credit. Cite as 'East Africa’s global history: a background text with comprehension and reflection questions for East Africa’s Global Lives', compiled by Ismay Milford and Anna Adima for Another World? East Africa and the Global 1960s.

Click here to download a printer-friendly pdf version of the teaching resource

East Africa’s global history: a background text with comprehension and reflection questions for East Africa’s Global Lives

How do the twentieth century’s global historical shifts appear if we approach them from or through East Africa’s regional history? The life stories of East African women and men are one resource for answering this question. These individuals were active participants in global solidarity projects, governance, conflict and cultural production, in ways too diverse to neatly categorise. To understand the significance of different themes that emerge from their biographies, this short introduction provides background on the history of East Africa in the twentieth-century world.

Which East Africa?

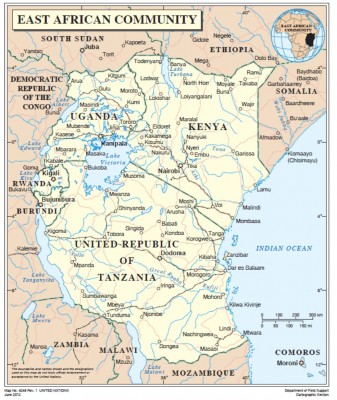

Definitions of geographical regions and their borders change across time and differ depending on who is being asked and with what factors in mind. The present-day East African Community is composed of Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda, but this political grouping would not have been predictable in 1950. At that time, regional integration in terms of infrastructure was most visible between Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, and to some extent Zanzibar, all of which were under British colonial administration. Colonial rule led to certain social and economic policies common across this region, as well as shared mechanisms for political oppression and its resistance. Yet longer histories of trade and migration cut across colonial borders, linking Indian Ocean coastal and island communities to those inland, whether through the trade of enslaved people or through exchanges of songs, food and architectural ideas. During the colonial period and either side of it, Swahili was a common language for people living in parts of what is now Tanzania, Kenya, Mozambique, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, linking spaces that were under British, Portuguese and Belgian colonial rule. At all times, communities living across formal borders have defined what these borders mean through their labour activities and family life. Rather than fixing a definition of East Africa, East Africa’s Global Lives includes individuals who lived and understood the region in different ways, reminding us of the limits of any regional definition.

East Africa’s ‘short’ twentieth century (1939-94) in historical perspective

Many of the processes and events described in East Africa’s Global Lives are concentrated in what we could call a ‘short’ twentieth century, stretching from the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 to the end of the apartheid regime in South Africa in 1994. During this period, almost every country in the East African region won independence from a European colonial power, including Tanganyika in 1961 (previously a UN Trust Territory under British administration), Uganda in 1962 (previously a British protectorate), Kenya in 1963 (previously a British colony), and Zanzibar in 1964 (previously a British protectorate). This was a prolonged (arguably unfinished) process, driven by and playing out in the cultural, social and intellectual spheres, as well as in the world of high politics, economics and law. Importantly, the history of this period of decolonisation in East Africa is not simply the story of the rise of nationalist party politics or of national transformation, but one of regional engagement with global events and power structures. Some of these are highlighted below.

Pan-Africanism and Afro-Asian solidarity

One major theme of East Africa’s twentieth century was its changing relationship with other parts of the African continent, the African diasporic community, and with countries in Asia and Latin America that shared experiences of colonial rule. While East Africa’s links to South Asia across the Indian Ocean were centuries old, the independence of India in 1947 led to efforts by Nehru’s government to forge ties with East Africa’s educated elite and new political parties, notably those calling for national independence. This was an important link to the politics of cooperation in newly independent countries and those looking towards independence, encapsulated in the much-mythologised Bandung conference of 1955 in Indonesia. East African countries were not invited to send delegations to this conference, but news of the bold anti-imperial declarations reached the region fast, especially through students studying in India or Egypt. This emerging anticolonial alliance had complex internal dynamics and was sometimes at odds with the priorities of the South Asian communities that had lived in East Africa for several generations.

Meanwhile, East Africa’s involvement in pan-African politics was also becoming more prominent. These politics had roots in the intellectual pan-African movement which took form in the late nineteenth century, and in the long resistance to Atlantic slavery that preceded it. In the 1930s and 1940s, intellectuals and activists from West Africa, the Caribbean and the United States crossed paths in Britain and France. But the pan-African movement looked increasingly to the African continent itself as the site for future projects of unity among African people – with some debate over definitions – especially after the famous Manchester conference of 1945. Growing numbers of East African students and activists travelling for education provided opportunities to work with West African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, and opportunities to hear and read more about francophone intellectuals and artists too, including Frantz Fanon and Sekou Touré. The All African People’s Conference of 1958, in Accra, the capital of newly independent Ghana, was a famously galvanising event, but some East Africans were also apprehensive about West African dominance of this solidarity project. They observed rivalries with North African leaders like Gamal Abdel Nasser, and wondered how to overcome the fact that the independence of East African countries was still not timetabled. Projects for regional cooperation, like the Pan-African Freedom Movement for East and Central Africa, were formed in this context.

All of these projects had afterlives or threads of continuity after independence. New African governments rallied around opposition to the racist regimes in Southern Africa and the war in Vietnam, while cultural initiatives like the Afro-Asian literary journal Lotus thrived.

Reading comprehension questions (based on biographies):

-

How did East Africans contribute towards independence struggle in Portuguese colonies such as Goa (now part of India) and Mozambique? (see Pio Gama Pinto)

-

What organisations and events facilitated cooperation between African trades unions? (see Pio Gama Pinto and others)

-

How did events on mainland East Africa affect politics in Comoros? (see Abdou Bakari Boina)

-

On what parts of the world did MOLINACO’s international campaign focus? (see Abdou Bakari Boina)

-

What pan-African connections and debates were fostered through the literary journal Transition? (see Rajat Neogy)

Research and reflection questions:

-

At what historical moments, or in what sources, does the history of pan-Africanism and Afro-Asian solidarity look like a history of conflict and compromise, as well as a history of cooperation? (refer to the above biographies, as well as those of Boloki Chango Machyo and Arthur Aggrey Ochwada)

-

Research task: Explore the interactive visualisation of conference attendance created by the Afro-Asian Networks Research Collective, at https://afroasian.mediaplaygrounds.co.uk/. What conclusions can you draw about the where and when Afro-Asian conference activity was at its most intense? What were the limits of this conferencing era, particularly in terms of who could not attend? What are the limits of this method of presenting data (i.e. what can these maps not tell us and how might we explore these things further)?

Further reading

-

Hakim Adi, Pan-Africanism: A History (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018).

-

Afro-Asian Networks Research Collective, ‘Manifesto: Networks of Decolonization in Asia and Africa’, Radical History Review, 2018:131 (2018), 176–182.

The United Nations

Alliances between countries that had recently gained political independence also formed at an international level in the UN. Given that UN membership was reserved for independent states, the period from its 1946 founding through to 1994 witnessed a dramatic transformation in the make-up of this international organisation. East African representatives came to play important roles in UN institutions, from the FAO to UNESCO, shaping policies and transferring their own knowledge of the challenges faced in the region. East African states formed broader regional alliances, sometimes with radical ideas about how to reconstitute a global order that appeared to reproduce the structural inequalities of the colonial, for example the New International Economic Order. The UN had not always supported the independence of East Africa states, however. The East African lives and livelihoods lost through service in the Second World War (1939-45) gave extra ammunition to demands for political participation and for social and economic opportunities, which could be channelled through the UN. However, colonial powers were able to use their positions on the UN Security Council to veto debate on these issues. While both the war and the formation of the UN appeared to reaffirm an ideal of self-determination, whereby people directly choose the government under which they live, this did not simply translate into improved rights for East African citizens.

Reading comprehension questions:

-

How did discussion about East African gender politics play out in UN forums and shape UN discussions? Conversely, what did UN membership mean for East African women? (see Julia Auma Ojiambo and Margaret Kenyatta)

-

What were East African contributions to UN scientific bodies and what difference did the UN make to environment and agriculture in East Africa? (see Wangari Maathai and John Kabwimukya Babiiha)

Research and reflection questions:

-

Through an internet search, identify when and how East African states and individuals took part in the UN’s various agencies and bodies (e.g. UNESCO, FAO). Referring to the biographies highlighted above, what can you say about where East Africa’s opportunities for leverage lay within the UN?

-

Reflect on the narrative of the UN’s mid-century expansion presented on the organisation’s website. How would you describe this narrative? What alternative interpretations could be suggested to describe the role of the UN in East Africa across the twentieth century?

Further reading

-

Adom Getachew, Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019).

-

Eva-Maria Muschik, ‘Managing the World: The United Nations, Decolonization, and the Strange Triumph of State Sovereignty in the 1950s and 1960s’, Journal of Global History, 13:1 (2018), 121–144.

The Cold War

East Africa never became what historians would later describe as a Cold War ‘hotspot’, where Cold War superpowers held direct stakes in armed conflict. But there is no doubt that East African women and men engaged with this global conflict in many ways, from its early manifestations in the 1950s to the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989. The political manifestos of East Africa’s first post-independence leaders used the capitalist Western bloc or ‘First World’ and the communist Eastern bloc or ‘Second World’ as reference points: most plotted a political trajectory that refused alignment with either bloc, thus becoming part of the group of countries known as the ‘Third World’. The politics of non-alignment were complex in practice, however, especially when it came to international trade and exchanges of students or expertise. This frequently proved a source of tension between political parties and individual politicians across East Africa. Ordinary people felt the Cold War in post-independence towns and cities, as liberation groups, intellectuals and intelligence officers with Cold War backing were hosted by East African states, perhaps most famously in 1970s Dar es Salaam. Literature from Maoist China and anti-communist propaganda found its way into bookshops, while youth groups and trades unions corresponded with Cold War international organisations seeking their membership.

Reading comprehension questions:

-

Which trades union organisations played a role in East Africa’s experience of the Cold War? Where did these organisations stand on the ideological conflict of the day? (see Arthur Aggrey Ochwada)

-

What impact could studying abroad in the ‘non-aligned’ world have on East African intellectuals? (see Joseph Robert ‘Sepp Meier’ Bikobbo Mugayo)

-

What ideas about Africa and socialism could be heard at Cold War-era international youth conferences? (see Boloki Chango Machyo)

Research and reflection questions:

-

Was the ambition for independence from Cold War funding and sponsors distinct from an ambition for political independence from colonial powers, or did it amount to the same thing? Consider different contexts and different individuals, using biographies under the tag ‘Cold War’.

-

Explore the writings of Guyanese intellectual Walter Rodney (https://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/rodney-walter/index.htm) and consider what they can tell us about the ideas circulating in 1970s Dar es Salaam. Did Dar es Salaam reflect the dynamics of the Cold War or, on the contrary, were its debates fundamentally about what was happening in East Africa?

-

How did the Cold War shape music, literature, and the arts in East Africa?

Further reading:

-

Noah Tsika, ‘The Cold War’s unfinished legacy’, Africa is a country (2020), at https://africasacountry.com/2020/09/the-cold-wars-unfinished-legacy

-

Duncan Omanga and Kipkosgei Arap Buigutt, ‘Marx in Campus: Print Cultures, Nationalism and Student Activism in the Late 1970s Kenya’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 11:4 (2017), 571–589.

Culture and Literature

Culture and literature played an important role during this decade in East Africa, a time when countries were gaining their independence from Britain. At the same time, pro-Black movements such as Négritude and pan-Africanism were sweeping across the continent. Writers in East Africa drew inspiration from this, which is reflected in their work. Literature flourished in this period, with novelists, poets, and playwrights expressing their hopes for independence in their writing. In June 1962, Makerere College in Uganda hosted the now-famous African Writers Conference (officially called the ‘Conference of African Writers of English Expression’). Writers from all over Africa attended this event, including Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Debates centred around the following questions: What form should African literature take? Should African literature be written in African or European languages? Does African literature have to be written by Africans? These debates determined the direction African literature would take the following decades.

Important Ugandan literary figures in the 1960s included the poet Okot p’Bitek (Song of Lawino) and the novelist and playwright Robert Serumaga (Return to the Shadows); in Kenya, novelist and playwright Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (Weep Not Child; The River Between) and novelist Grace Ogot (The Promised Land; Land Without Thunder); and in Tanzania, the poet Shabaan Robert (Koja la lugha) and novelist Muhammad Said Abdulla (Mzimu wa Wate wa Kale).

Reading comprehension questions (based on biographies):

-

What role did Transition magazine play in the East African literary scene in this period (see Rajat Neogy)

-

Why do we know of fewer women writers in this period, in comparison to male writers (see Barbara Kimenye)

Research and reflection questions:

-

Consider other art forms, such as visual art and music. How did the events of the 1960s (independence, the Cold War, globalisation) impact their content and creation? (A starting point would be Daniel Owino Misiani’s biography)

-

Consider the local political climate in individual African countries in this time, and look at the nature of their regimes and government (Uganda under Milton Obote; Kenya under Jomo Kenyatta; Tanzania under Julius Nyerere). Explore how writers were affected by the different regimes, and how their work was impacted.

Further reading:

-

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Birth of a Dreamweaver: A Writer’s Awakening (New York: The New Press, 2016).

-

James Currey, Africa Writes Back: The African Writers Series and the Launch of African Literature (Oxford: James Currey, 2008).