Margaret Kenyatta (1928-2017)

Nairobi City Mayor and KANU women's wing leader

Margaret Wambui Kenyatta was born on 16 of February 1928 in Nairobi. She was sister to Peter Muigai Kenyatta and daughter to Grace Wahu and the first President of the Republic of Kenya, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta. Margaret was educated at Alliance High school in Kikuyu and later on went to Kenya Teachers Training College in Githunguri, 1948-52. She worked as a telephone operator and bookkeeper, before joining KANU on its formation in 1960. Margaret was then elected as KANU Kiambu branch Assistant Secretary and later Secretary, serving from 1961 to 1962. During the period, she also doubled up as a Women’s Wing Leader and Chairperson for Kenya Women’s Seminar. In 1963, she was elected to Nairobi City Council as a councillor representing Dagoretti.

Women's organisations

Margaret was elected President of Kenya National Council of Women (KNCW) when it was first inaugurated in 1963. The inauguration meeting was to be attended by representatives from the foremost women’s bodies, such as the East African Women’s League, Maendeleo Ya Wanawake (women’s development) Organisation (MYWO), homemakers and girl guides. Margaret also represented Kenyan women overseas at the United Nations in 1965. In 1967, Margaret was understood to be one of the most widely travelled, experienced and competent leaders in Kenya. While in the USA, she interacted with a high-ranking US government official, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs, Katie Louchheim and met women from all over the world. For instance, during the visit, they were joined at the luncheon by J.L. Hunter, President of the Washington chapter of the League of Women Voters. Hunter was the first African-American to the office. Margaret also attended the International Council for Women.

During her early life, Margaret dedicated her time to social work. While at school, she was interested in the welfare of her people and community’s development. She had the hope of becoming a teacher and this is evident in her working as an untrained teacher. At some point in her early life, she was invited to the opening of a girls’ boarding school in Embu, where she emphasised the importance of educating girls as future wives and mothers because it was they who laid the educational foundation for children.

As the President of the KNCW, Margaret endeavoured to work to bring together women’s associations in Kenya, and to promote the welfare of mankind and of the nation as a whole, of the family and of the individual. Consequently, this would encourage voluntary social services in the country. For her, the council policy was to exclude political and religious questions of a controversial nature while providing home and household training and management for girls so as to bring about physical and moral nourishment.

Political divisions emerge

Margaret always kept the Kenyatta family together through written correspondences and occasional visits when her brother Peter Muigai and his father, Jomo Kenyatta were detained. Given her attachment to her father, it is not surprising that it was Margaret who joined politics soon after Kenya’s independence. As it was earlier observed, Margaret was a councillor of Nairobi City Council in 1963, later on the city’s mayor from 1970-76, before resigning on her appointment as Kenya’s Permanent representative to the United Nations Programme on Environment (UNEP) at the age of 48 years. Analysts interpreted the appointment of Margaret as a way of moving matters off the dead centre and opening the way for elections. This was because during her reign as mayor, the city was faced with many challenges ranging from poor sanitation to inadequate health, housing and corruption. Subsequently, there had been a lot of in-fighting among councillors jockeying for positions. When mayoral elections were to be held in 1976, a rift between the incumbent and her deputy, Councillor Andrew Ngumba, was witnessed. On the eve of elections, which were due in August 1976, Local Government Minister Robert Matano postponed the elections indefinitely, a move seen by pro-Ngumba supporters to spare the incumbent, Margaret, a possible defeat.

In mid-1976, Margaret had cold feet leaving the city hall. Following a series of delegations from women representatives in the city, she announced that she had changed her mind about quitting politics. Her reason was that she had to heed the wishes of the women delegations. This reason was not taken seriously by Ngumba and his supporters, who had a cause for concern when some members of the Nairobi KANU branch, some of them councillors, announced that they had decided that Margaret should be re-elected unopposed and even threatened Ngumba with expulsion from the party if he stood against her. Ngumba refused to be intimated and for good reason: according to his arithmetic, he could easily defeat Margaret at the polls. The mayoral elections involved only city councillors as voters and Ngumba figured that he had more than the necessary number to win a straight fight with Margaret. This was never to happen as the minister for local government called off the elections indefinitely a week before they took place. The elections were not held until Margaret left to take up a new appointment at UNEP headquarters. Indeed, during her reign as the Mayor, she was a symbol of how toothless the City Council was.

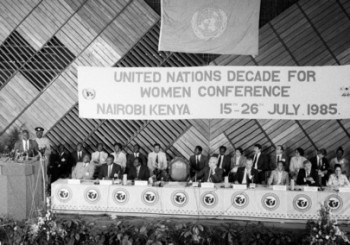

Women in the United Nations

The status of women in independent Kenya was little different than in the colonial era. The dominant women’s organisation was MYWO, which was muzzled and became toothless- (Nzomo, 2002). Women’s participation in politics was mainly through singing and dancing for political leaders, among other forms of entertainment. In the 1970s, Kenyatta’s government laid down rules for women’s groups in a bid to closely monitor and control them. Chazan (1989; 186), notes that state policies towards women in Kenya exhibited varying degrees of discrimination and coercion. She concludes that whether post-colonial states in Africa are sites of gender struggles or not, the concept of gender cannot be left out of the analysis of politics. Consequently, a more fruitful approach would be to consider the ways in which state formation and practices are all gendered and to analyse their involvement in these state processes and practices. Kavetsa Adagala (1985; 7) observes that Nairobi was chosen to host the Women’s Forum following the Women’s Decade (1975-1985) because while supporting Israel, South Africa and the USA in the UN conferences in Mexico City and Copenhagen, Kenyan women representatives were against apartheid and the politics of Palestine being dragged into women issues. However, Adagala points at pertinent issues that eventually led President Moi to settle on Margaret. First, it was the rejection of Prof. Wangari Mathaai who was perceived as too rebellious – a divorcee who was publicly accused of adultery. As result of the UN Decade, the official governmental section (Women Bureau) settled on Eddah Gachukia, then chair of an NGO organising committee, who was accused of tribal bias in the selection of sub-committees to write on women issues in Kenya and of ignoring the plight of rural women. Instead, Gachukia appointed wives of rich and prominent men. Secondly, the government’s lack of justification for having men as heads of women delegations at national and continental meetings (Women Decade) which culminated in the women’s forum held in Nairobi, finally led to the appointment of Margaret. According to Adagala, Margaret knew little of the NGO’s history and the context of the Women Forum and therefore she was not the ideal person to represent women. This implied that she was a proxy for her father.

From Godwin’s interview with Margaret on the eve of the annual KNCW conference which was held in Nairobi, it was evident that the way Kenyan women politicians are discussed by the general public and fellow women keeps them squarely in the domestic realm and absolves men of their responsibilities as representatives of the people. World over, and in Kenya to be precise, women have been socialised to believe that men are more suited to political leadership. In Nairobi, voters were often more forgiving of male politicians’ flaws than of those of women. Women were to prove that they are good wives and homemakers before they were elected.

In a nutshell, Margaret’s life sheds light on how women can derive political legitimacy by framing themselves as ‘social workers’ and feminists for their specific communities and, therefore, they are asked by the masses to support the poorest and the most vulnerable of their communities. Yet, Margaret Kenyatta’s personal relationships influenced grassroots, national, continental and even global politics on women’s issues.

Archives and online sources

Kenya Weekly

The Weekly Review

The Standard

Further reading

Adagala Kavetsa, ‘Kenya Before the Conference’, Off Our Backs, vol. 15 no. 11 (1985).

Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong and Henry Louis Gates (eds), The Dictionary of African Biography.

‘Kenyatta, Margaret (1928-2017)’, in Anne Commire and Deborah Klezmer (eds.), Women in World History: A biographical Encyclopedia.

M. P. Nzomo, ‘Kenyan Women in Politics and Public Decision Making’, in G. Mikell (ed.), African Feminism: The Politics of Survival in sub-Saharan Africa, (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997), pp. 232-75.

E. G. Wilson (ed.), Who's Who in East Africa, 1965-66 (Nairobi: Marco Publishers, 1966).